[This is a re-post of a blog post I first wrote and posted in 2010-11-12 in Monolith149 Daily. I’ve made some slight edits to the text.]

I was the director of the planetarium at the time and had received a letter from NASA that they were broadcasting live coverage of the Voyager 1 encounter via satellite.

When I was a kid, reading library books about the solar system, there would often be a chapter at the end of the book on the Grand Tour of the Planets. A favorable alignment of the four gas giants, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, would allow a single spacecraft to visit each of them using gravitational assist, in the distant future of the 1980s.

Fast-forward to 1977, either 5 Sep 1977 (Voyager 2) or 20 Aug 1977 (Voyager 1), I forget which.* It’s morning and I’m lying on the sofa after being at the museum’s observatory all night. I’m watching the Voyager spacecraft launch on TV. With those launches, the Grand Tour became a reality and Voyager 2 visited all four planets.

However, it was Voyager 1 that visited Jupiter and Saturn first. The spacecraft stole some of Jupiter’s orbital momentum, causing Jupiter to fall just a little bit toward the sun, as it accelerated on to Saturn

The event was going to happen on 12 Nov 1980. There was no NASA channel at the time so I had to call the local cable operator (Cox) and ask them to tune into the particular satellite and transponder that NASA had arranged and to feed the coverage out over a spare channel on their cable plant. It took some convincing since they were reluctant to actually commit a channel, even for a one-time event. In the end, I think I ended up talking to a guy in a control shack, probably running their dish farm, who impressed me as not wanting to be bothered with events from other planets. My memory is that I never got an absolute firm commitment but something more like a shaky okay which was more than a little worrisome.

Next, it was necessary to find a video tape recorder and it turned out there was one I could borrow from the board of education. I drove down to their dusty equipment warehouse to pick it up. Or maybe it was just the road by the warehouse that was dusty. It was an old ¾-inch U-Matic machine, a video cassette size frequently used by TV stations in those days. The ½-in cassettes were just starting to become popular as the VHS vs. Betamax battle was raging.

We hauled the recorder over to the house of one of our staff members’ parents to record the coverage since they had cable. The encounter was in the middle of the day and several of the planetarium staff were crowded into their den, watching the show.

It was a heady time indeed as we watched those black and white pictures scroll slowly in because the data download rates from the space probe were slower than the modems of the time. Of course they were not digitally post-processed yet—they were pretty raw images—so there were just the beginning hints of some of the amazing sites to come. The coverage cameras showed ecstatic scientists watching the same images appear on their control room monitors and there were several interviews with Ed Stone, Carl Sagan and others who were seeing their own life-long fantasies come true.

Sometimes you suddenly arrive at those moments when you get goosebumps and a lump in your throat, when you know you’re experiencing pinnacle achievements in human history. This was one of them.

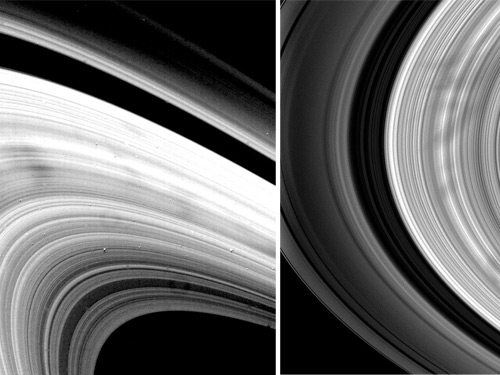

As the pictures crawled in, I believe it was possible, even in those first images, to see the spokes in the rings, the braided F-ring, and some of the other jaw-dropping, never-imagined features of Saturn up-close.

After recording the fly-by, we borrowed a TV from one of the local TV shops. It was just a standard 19-in, or slightly larger, CRT. We set it up in the planetarium and opened to the public for a replay of the “live” Voyager-Saturn encounter. I remember we had a bit of difficulty because the video tape recorder had a separate RF modulator, the size of a small, chunky game cartridge, that had to be physically plugged into the back of the machine before we could get a signal to the TV.

I guess we had enough lead time to advertise the event using the usual TV and newspaper avenues because there was a pretty good turnout. There were college professors, amateur astronomers and many other enthusiastic folks from the community who were just as thrilled as the crew at JPL to see these first images coming back from the ringed planet, even though our replay was delayed by hours.

As I recall there were encounter events over two or three days as Voyager flew by some of Saturn’s moons and made its way across Saturn’s “miniature solar system,” so we had probably two and possibly three nights of replay.

Today Voyager 1 is over 115 AU (astronomical units) from the Sun. By definition, the Earth is 1 AU from the Sun. Pluto is, on average, about 40 AU distant. Voyager 1 is the most distant, active spacecraft in the solar system and it’s still collecting and transmitting data.

“In four to six years, Voyager 1 is expected to cross beyond the heliosheath, the outer layer of the bubble around our solar system that is composed of ionized atoms streaming outward from our sun,” reports a news release from NASA this past October [2010].

We’ve come a long way from those solar system books from the library, written in days when artists never even thought to include clouds when illustrating the Earth as seen from space. I’ve been amazed to see so many of those funny but always awe-inspiring artist’s conceptions come to reality. It will be fascinating to see which ones come next.

* * *

It was just past the turn of the century and I’d never thought about it before even after a couple of years or so. It was a friend who pointed out to me that the two vehicles sitting in our driveway were a Voyager and a Saturn.

__________

* No that’s not a typo. Due to the solar system and mission mechanics

involved, Voyager 2 was actually launched before Voyager 1.

Image Credit

Ghostly Spokes in the Rings

Scientists first saw these somewhat wedge-shaped, transient clouds of tiny particles known as “spokes” in images from NASA’s Voyager spacecraft. They dubbed these features in Saturn’s B ring “spokes” because they looked like bicycle spokes. An electrostatic charge, the way static electricity on Earth can raise the hair on your arms, appears to be levitating tiny ring particles above the ring plane, but scientists are still figuring out how the particles get that charge as they analyze images from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft.

The image on the left was obtained by Voyager 2 on Aug. 22, 1981. The image on the right was obtained by Cassini on Nov. 2, 2008.

Image credit: NASA/JPL and NASA/JPL/SSI